The 5 Ways Interior Designers are Making Today’s Buildings Greener

Interior design is like tending a garden – you nurture the capabilities of a space, weed out the clutter, and adjust your interventions to fulfill changing needs over time.

Even the newest buildings coming online today could have better green building performance. The client, architect and construction team may try to optimize the building envelope, systems, and technologies, and yet still leave some unrealized opportunities for sustainability. Sometimes an interior designer is on board at the start to help guide green solutions as an integral part of the planning, and sometimes the framework is set before the designer is engaged. Either way, human-centered design can make an enormous difference in sustainable outcomes.

The design of a building is always in the process of becoming, from the moment someone saw the need. In the first flush of inspiration, its potential is unlimited. As we sketch it, model it, and build it, we may think the possibilities become narrower. We sometimes forget the role of the interior designer in this “ever-becoming” process: soon after the first contractor has gone home, and into the unlimited future, the designer sees new lives for its spaces and new colors, forms, and surfaces that will touch people in ways unimagined at the beginning.

Stewart Brand of The Long Now captured some of this in a book called How Buildings Learn, the thesis of which is that buildings often start out with a with a form that is more or less “fit for purpose,” but these same buildings somehow find ways to better meet their users’ needs over time. In some cases, the purpose or use of a building changes, and it needs to, in Brand’s word, “learn” how to accommodate the new purpose. Can a building really learn?

One answer to the question raised by the book’s title – how, exactly, an inanimate object can learn – is interior design. Buildings, like everything else in our universe, are always changing. Some of that change is too slow to observe. Structure and enclosure changes are infrequent because we need stability. We need to know the building is going to withstand the forces that may erode it. However, we often find reason to tweak it – add columns and a beam when we want to take out a bearing wall, or enlarge a window opening, for example. Things we do with greater frequency include repainting interior walls, or changing the furniture, among other things. Brand tells us this range from structure to decorative objects simply constitute different “layers” of the building, and some layers change more easily and rapidly than others.

If a building is going to learn it needs a caring gardener, a green steward who knows what to keep, add, and subtract in a way that conserves natural resources and supports the health and well-being of occupants. Read on to see how the interior designer’s stewardship impacts the key design variables of Orientation, Daylighting, Interior Design Materials, Kitchen and Bath, and Thermal Comfort.

Greener Orientation

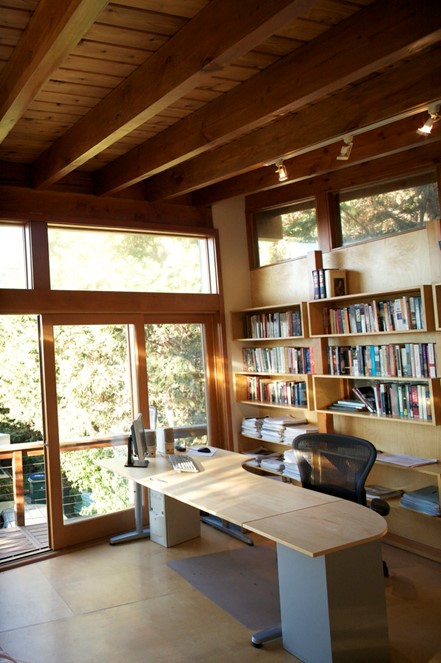

Decided early in the design process and critical not only to thermal performance but also to occupant satisfaction is the placement of the building with respect to the sun path diagram. The simplest of building shapes, a rectangle, with its long axis parallel to the greatest solar exposure gives us a cascading series of decisions about placement of activities and their need for natural light, shade, and glare control. Daylighting strategies take advantage of orientation and manage unwanted solar heat gain.

Natural Daylighting

Closely connected to solar orientation is the family of strategies to control and bring natural light into the interior spaces. Careful management of color selection allows the designer to employ reflective and color-absorbing surfaces to maximize natural light and minimize non-energy-using artificial lighting in the illumination approach. White and light-colored surfaces amplify the natural light waves. In addition to color, interior light shelves use the “bounce” effect to both maximize daylight entering the space and cut off unwanted radiant heat at the perimeter. Interior designers experiment with modeling these effects using cardboard study models and AutoCAD, SketchUp, or Revit software.

Greener Materials – low carbon, local, and no add-ons

While continuing strategies of selecting and specifying materials that are recycled (a new direction is the diversion of ocean-bound plastic into repurposed furniture components in the redesign Aeron Chair Portfolio by the Herman Miller Corporation) or not harmful to the environment of their extraction and manufacture, and avoiding vinyl compounds whose production may have harmful effects on ecosystems and people, interior designers today are even more focused on the embodied energy represented by their choices. Some materials like aluminum and some plastics have an outsized carbon footprint due to the large amount of fossil fuels burned in their production processes and can in many cases be replaced by wood or other natural materials. Today’s designers are avoiding mistakes of the recent past, like adding decorative materials that may have a good “eco-story” like rapidly renewable source material, whereas the most sustainable approach is not to add anything at all. Other materials are carefully vetted for point of origin within a local radius, to cut the fossil fuels burned in their transport from far-away locations to the job site. Finally, since much of the work of sustainable interior designers is in the realm of Stewart Brand’s short-cycle “layer” due to turnover of workplace leases and changing trends in hospitality design, minimizing construction waste plays an even larger role in the work of interior design than in architecture and construction generally.

Green Kitchen and Bath

The floor plan location of the kitchen, bath, laundry room, and other heat-generating functions in residential interior design is no longer the default assumption it once was. Careful adjacency planning of these elements to maximize natural heat dissipation and reduce the burden on fossil fuel-burning air conditioning systems. Relationships to both occupied areas and the thermal envelope of the building adds to the overall energy efficiency of the project. The kitchen’s high concentration of storage cabinets and countertops means it is another opportunity for material selection to favor natural materials over process-heavy composites.

Thermal Comfort

Human-centered design begins with adapting environments to better support people’s needs. Nothing is more central to this than helping people, who operate best within a relatively narrow band of possible temperature and humidity levels, achieve a sense of comfort in their living, working, and entertainment settings. Interior designers know that these variables of relative heat, humidity, evaporation, and air movement are subtly inter-related and adjusting these variables allow us to feel comfortable within a wider range of conditions. The key designer’s tool here is the psychrometric chart, which illustrates temperature, humidity and air movement in combination. In the twentieth century, architects and mechanical engineers widened the comfort range using fossil fuel-burning heating and air conditioning systems, overpowering the environment with technology. Today’s interior designers work with all team members to leverage sustainable means of tempering extremes of heat and humidity through natural ventilation. Small courtyard fountains and landscaping add evaporative cooling.

DESIGN INSTITUTE OF SAN DIEGO

Design Institute of San Diego offers a Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) in Interior Design Degree Program and a Master of Interior Design (MID) in two and three-year tracks. You’ll learn design fundamentals as well as innovative applications from a faculty of practicing interior designers – and get to experience the profession first-hand as an “extern” at an interior design firm. With a degree from Design Institute of San Diego, you’ll be prepared for a rewarding career in interior design. Learn more.

IMAGE CREDITS

1 “Green” by jinkazamah is licensed under CC BY 2.0

2 “Drought Tolerant Landscaping” by Jeremy Levine Design is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

3 “Mazzali: WIND canopy bed / il letto a baldacchino WIND. SKY wardrobe. Bedroom area” by MAZZALI bespoke italian furniture is licensed under CC BY 2.0

4 “Urban Cabin – Writer’s Office” by Jeremy Levine Design is licensed under CC BY 2.0

5 “Interior View” by Jeremy Levine Design is licensed under CC BY 2.0

6 “bath-room” by jinkazamah is licensed under CC BY 2.0

7 “Thermal Insulation” by zeevveez is licensed under CC0 1.0